The semester is over at Wofford. Though I was on leave from my normal teaching duties, I did supervise the independent work of three students, one of whom (Jennifer Coggins) wrote an excellent honors thesis on Richard Nixon, the southern strategy, and school desegregation. For her, of course, Nixon was fairly distant history. For me, Nixon is memory. I always tell my students that Nixon is the first president I really remember and that the adult version of me is no more taken with him than the child version was, so they should take my mixture of memory and history with an appropriate grain of salt.

Last week brought a jarring reminder of the relevance of scholarly work like this thesis. In short (and I'm simplifying a 50 page argument), in the 1968 campaign, Nixon employed what has been called the "southern strategy" and the rhetoric used in the election had real consequences for Nixon administration policy regarding school integration.

The "southern strategy" was the attempt to exploit politically LBJ's full embrace of civil rights in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. The thinking was that disaffected Democrats (especially, but not exclusively, from the south--think Archie Bunker) could be convinced to vote Republican by the used of racially coded rhetoric that would signal sympathy with their opposition to the civil rights movement.

The trick, however, was to do so without being too obvious about it, since that ran the risk of alienating independents and Republicans who supported civil rights. So Nixon used phrases such as "law and order" which had no inherent racial meaning, but had become racially charged due to the rioting after Martin Luther King's assassination in April 1968 and the rise of militant groups like the Black Panthers.

Choosing the right words, therefore, could send different messages to different audiences: opponents of civil rights could see a rebuke to the movement, while others could see a non-racial appeal for social stability in a tumultuous time.

Last Thursday, the New York Times ran a story about a proposed ad campaign, funded by a conservative billionaire named Joe Ricketts, to use Rev. Jeremiah Wright to try to discredit President Obama. Using Rev. Wright would not necessarily raise comparisons to Nixon's southern strategy. In fact, nothing in the Times article did for me. But the Times helpfully included a link to the entire proposed ad campaign document.

Being a historian, I welcomed the chance to read the primary source. Not surprisingly, the authors were aware of the potential racially charged nature of the proposed ad. To pre-empt any such charges, they proposed getting "an extremely literate, conservative African American in our spokesman group," as well as using focus groups to test how the ad came across. The focus group would help identify what might seem racist to viewers.

Again, nothing too overtly suggesting the southern strategy. In fact, for a moment, I thought that the idea was to insure that there was truly nothing racist about the ad. Then came the explanation that the focus group would help them in "making fine-tuning adjustments in wording and visuals to increase the impact, while lessening any elements that could reasonably be deemed 'racist.'"

"Lessening." In that one word, we see the essence of the southern strategy.

The paragraph begins with the assumption that the "instant response liberals give to any attack is to deem the attack as racist." But those are not the people the ad's authors care about. The perception that they are trying to influence is not that of knee-jerk, partisan liberals. The focus group is there to tell them what could reasonably be deemed racist.

They take as a given that the focus group may well think parts of the ad "could reasonably be deemed 'racist.'" And in response they would tweak the ad to lessen those elements.

Not "eliminate," but lessen.

As it was with the southern strategy, the concern is perception. The challenge is to use a racially charged attack and try to make it not look racist to people who will be offended by its racism. So you identify and lessen the racist elements. But you don't eliminate them, because that would defeat the purpose. You are also speaking to another audience, and they need to be able to perceive what will motivate them.

Four years ago, Rick Perlstein wrote a book called Nixonland, that argues that Nixon shaped the political world we now live in. That is probably an overstatement. But when it comes to the southern strategy, some people are clearly still living in Nixonland.

Last week brought a jarring reminder of the relevance of scholarly work like this thesis. In short (and I'm simplifying a 50 page argument), in the 1968 campaign, Nixon employed what has been called the "southern strategy" and the rhetoric used in the election had real consequences for Nixon administration policy regarding school integration.

The "southern strategy" was the attempt to exploit politically LBJ's full embrace of civil rights in the Civil Rights Act of 1964 and Voting Rights Act of 1965. The thinking was that disaffected Democrats (especially, but not exclusively, from the south--think Archie Bunker) could be convinced to vote Republican by the used of racially coded rhetoric that would signal sympathy with their opposition to the civil rights movement.

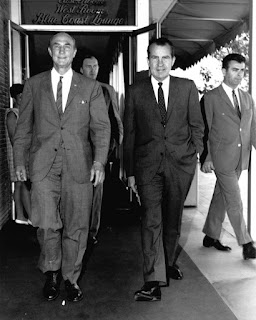

|

| South Carolina Sen. Strom Thurmond with Richard Nixon during the 1968 campaign. |

Choosing the right words, therefore, could send different messages to different audiences: opponents of civil rights could see a rebuke to the movement, while others could see a non-racial appeal for social stability in a tumultuous time.

Last Thursday, the New York Times ran a story about a proposed ad campaign, funded by a conservative billionaire named Joe Ricketts, to use Rev. Jeremiah Wright to try to discredit President Obama. Using Rev. Wright would not necessarily raise comparisons to Nixon's southern strategy. In fact, nothing in the Times article did for me. But the Times helpfully included a link to the entire proposed ad campaign document.

|

| Title page of the memo by "Strategic Perceptions" |

Being a historian, I welcomed the chance to read the primary source. Not surprisingly, the authors were aware of the potential racially charged nature of the proposed ad. To pre-empt any such charges, they proposed getting "an extremely literate, conservative African American in our spokesman group," as well as using focus groups to test how the ad came across. The focus group would help identify what might seem racist to viewers.

Again, nothing too overtly suggesting the southern strategy. In fact, for a moment, I thought that the idea was to insure that there was truly nothing racist about the ad. Then came the explanation that the focus group would help them in "making fine-tuning adjustments in wording and visuals to increase the impact, while lessening any elements that could reasonably be deemed 'racist.'"

"Lessening." In that one word, we see the essence of the southern strategy.

The paragraph begins with the assumption that the "instant response liberals give to any attack is to deem the attack as racist." But those are not the people the ad's authors care about. The perception that they are trying to influence is not that of knee-jerk, partisan liberals. The focus group is there to tell them what could reasonably be deemed racist.

They take as a given that the focus group may well think parts of the ad "could reasonably be deemed 'racist.'" And in response they would tweak the ad to lessen those elements.

Not "eliminate," but lessen.

As it was with the southern strategy, the concern is perception. The challenge is to use a racially charged attack and try to make it not look racist to people who will be offended by its racism. So you identify and lessen the racist elements. But you don't eliminate them, because that would defeat the purpose. You are also speaking to another audience, and they need to be able to perceive what will motivate them.

Four years ago, Rick Perlstein wrote a book called Nixonland, that argues that Nixon shaped the political world we now live in. That is probably an overstatement. But when it comes to the southern strategy, some people are clearly still living in Nixonland.

Fascinating post, Mark. And I like your point to students about taking your assessment of Nixon with a grain of salt. I tell my students the same thing about my take on all presidents from Nixon forward.

ReplyDeleteYes, I'd like to think that as a historian I have a historically informed view of Nixon (and I actually credit him with having a lot to do with the end of the cold war via the long term effects of detente), but I also know I had a visceral reaction to him as a child. So full disclosure seems best.

ReplyDeleteExcellent!

ReplyDeleteI'm sure you've heard the Johnson tapes recently released where Johnson saved Nixon's ass, by hiding the fact that Nixon was negotiating with the Viet Namese leadership to stall the ending of the war.

You think Nixon would have done the same for Johnson?

http://consortiumnews.com/2012/06/14/admissions-on-nixons-treason/