In the last dozen years, I've traveled in two communist states, China and Vietnam, but I'd never been to a former communist state before last month. Other than its beauty and generally rich history, one of the appealing things for me about going to Prague was its place in 20th century history, particularly the Cold War. I've spent a large part of my career studying and teaching about the Cold War, and I was curious to get a taste of how people who lived under its shadow looked back on it.

Thus, I was particularly looking forward to our group's visit to the Museum of Communism.

Thus, I was particularly looking forward to our group's visit to the Museum of Communism.

I'm not sure exactly what I was expecting, but I wasn't expecting to be able to walk right past it without seeing it from the street. I should note for the record that I have a notoriously bad sense of direction, but in this case I was actually on the right street, Na Příkopě, and in the right place. But you can't see it from the street. The brochure helpfully points, however, that it is "above McDonald's, next to Casino."

That was my first clue that this would be no ordinary museum experience.

Once inside, that insight was continually reaffirmed. The first thing one notices is the prevalence of Soviet-era paintings and statues of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin. They had to go somewhere after the fall of communism, I suppose, and this is where at least some of them went.

One of the more interesting aspects of the museum for me was its willingness to examine the role that Czechs themselves played in the communist regime--particularly in its establishment in 1948. Unlike Poland and some of the other regimes in the old Soviet bloc, Czechoslovakia did not immediately fall under Soviet domination after World War II. Czech communists did fairly well in reasonably free postwar elections, and were included in the government of Edvard Beneš, the Czech nationalist who served as president from 1940 to 1948.

One of the more interesting aspects of the museum for me was its willingness to examine the role that Czechs themselves played in the communist regime--particularly in its establishment in 1948. Unlike Poland and some of the other regimes in the old Soviet bloc, Czechoslovakia did not immediately fall under Soviet domination after World War II. Czech communists did fairly well in reasonably free postwar elections, and were included in the government of Edvard Beneš, the Czech nationalist who served as president from 1940 to 1948.

The Czech reality is that homegrown communists were largely responsible for the imposition of communism after 1948, and the museum does not shy away from that fact.

It is also impossible to escape the Czech sense of humor, which permeates the entire museum. One of its displays, for example, is a communist-era shop, with almost nothing but a few nondescript cans on the shelves. Apart from being historically accurate, this is a highly comic choice, and it draws some of its power from its humor. It reminded me of the comments our wonderful Czech guide, Helena, would make whenever we'd pass an example of what she liked to refer to as "socialist architecture": "Coming up on the right is something no one should see," she'd wryly say. "So please, close your eyes."

The museum, like the Czechs themselves, does not play everything for humor, not at all. The re-creation of a secret police interrogation room and the display telling the story of the 1968 Soviet invasion make that readily apparent.

But the humor is never far removed from the tragedy. It is that sense of balance--the knowledge that comedy and tragedy are not opposites but integrally related parts of life--that gives this museum its character.

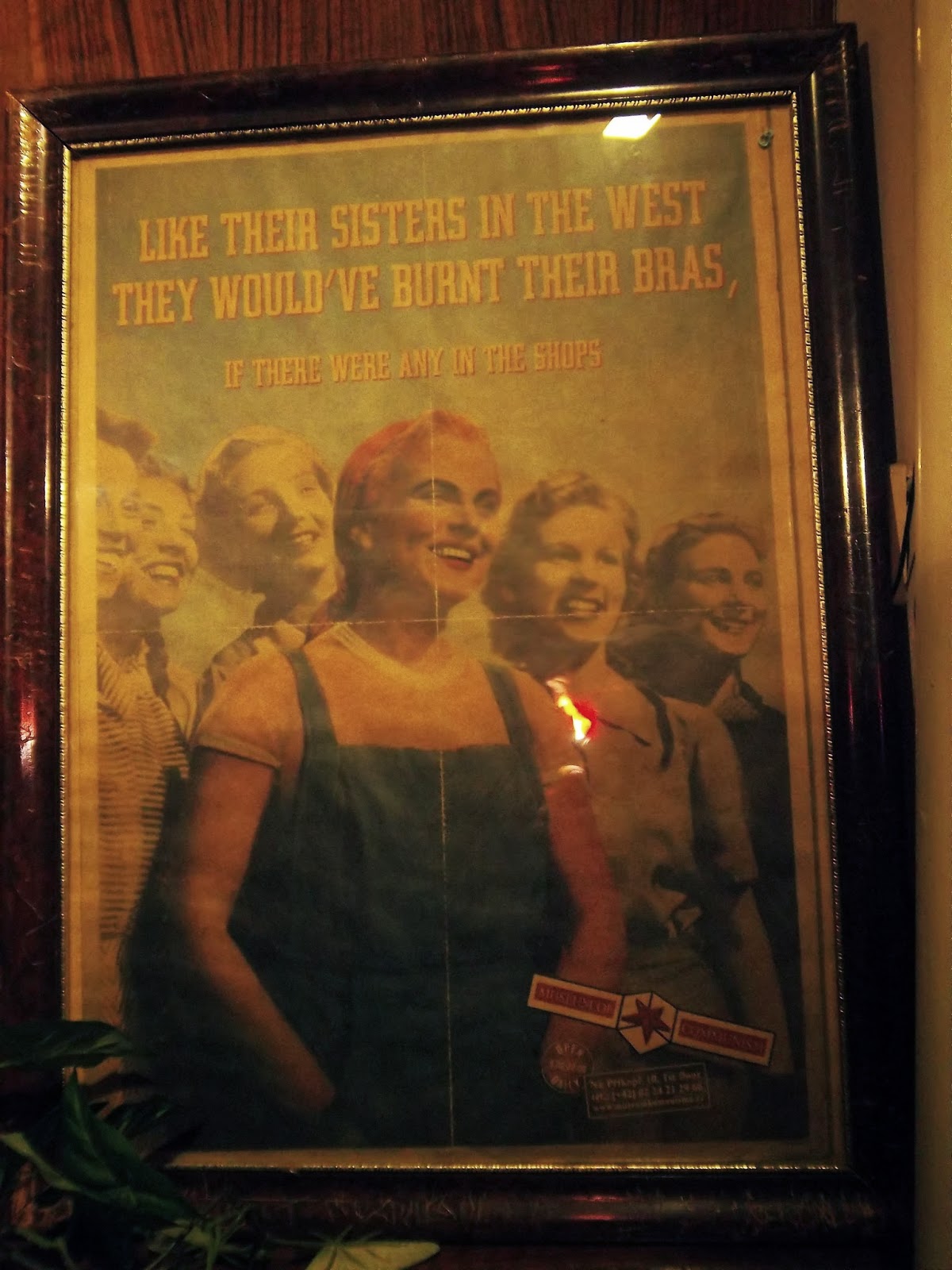

The absence of basic necessities is no joke. Nonetheless, walking down a hallway, you pass this picture tucked away in a little nook. At first it appears to be a bit of socialist realist "art," but then you read the caption: "Like their sisters in the west they would have burned their bras, if there were any in the shops."

Working my way through the museum, with its largely chronological approach leading inextricably to the amazing events of 1989, it was hard not to feel a touch of American triumphalism. You move from the dreary existence of the 1950s, through the brief optimism of the Prague Spring, only to see it brutally snuffed out by the Soviet invasion. You learn of the repression of post-'68 "normalization," and thrill at the rise of the Charter 77 dissidents and Vaclav Havel. Then the forty-year Czech nightmare comes to an end, and the people embrace the liberal values that the U.S. stood for in the Cold War.

Upon arriving at the gift shop and looking for some postcards to take home as souvenirs, I came across this one that seemed to capture just that pro-American sentiment. "We're above McDonald's--Across from Bennetton--Viva La Imperialism!"

It's a funny card. It takes such glee in mocking Lenin, one of the original critics of imperialism. I had to buy one.

I kept rummaging through the shop, and found a couple of collections of Soviet-era anti-American and anti-capitalist propaganda posters, spending far too much on them and rationalizing that I could make use of them in class one day.

And I made one last purchase. Another postcard, but this one had a message significantly different from "Viva La Imperialism!" The two of them together tell, I think, a meaningfully different story than either one does in isolation.

"Come and see the times when Voice of America was still the voice of freedom." Now there's a quick cure for the American tourist's sense of triumphalism. I have no way of knowing when exactly this card was first produced and therefore can only guess at what particular events or policies produced it, but there is no escaping its message of disillusionment with the post-cold war U.S.

There was that sense of balance again. Even in a museum dedicated to demonstrating the failure of the ideology of America's Cold War nemesis, there was a refusal to indulge in a mirror-image worship of America's victorious ideology.

What I took from the museum, what I took from much of the reading I did to prepare for the trip (in particular works by Ivan Klima and Milan Kundera), what I took from my admittedly brief and superficial exposure to the Czechs, is that it is the uncritical embrace of ideology--perhaps as much as the content of that ideology--that leads people to destructive fanaticism. If we take our ideas so seriously that we cannot laugh at ourselves and see the humor in the sometimes absurd manifestations of our own beliefs, that is when we lose our way. I'm sure that's not a uniquely Czech view of life, but I saw enough of it there to associate it with the lovely city of Prague. That, as much as the beauty of the city itself, is what I think I'll most remember.

Thus, I was particularly looking forward to our group's visit to the Museum of Communism.

Thus, I was particularly looking forward to our group's visit to the Museum of Communism.I'm not sure exactly what I was expecting, but I wasn't expecting to be able to walk right past it without seeing it from the street. I should note for the record that I have a notoriously bad sense of direction, but in this case I was actually on the right street, Na Příkopě, and in the right place. But you can't see it from the street. The brochure helpfully points, however, that it is "above McDonald's, next to Casino."

That was my first clue that this would be no ordinary museum experience.

Once inside, that insight was continually reaffirmed. The first thing one notices is the prevalence of Soviet-era paintings and statues of Marx, Lenin, and Stalin. They had to go somewhere after the fall of communism, I suppose, and this is where at least some of them went.

One of the more interesting aspects of the museum for me was its willingness to examine the role that Czechs themselves played in the communist regime--particularly in its establishment in 1948. Unlike Poland and some of the other regimes in the old Soviet bloc, Czechoslovakia did not immediately fall under Soviet domination after World War II. Czech communists did fairly well in reasonably free postwar elections, and were included in the government of Edvard Beneš, the Czech nationalist who served as president from 1940 to 1948.

One of the more interesting aspects of the museum for me was its willingness to examine the role that Czechs themselves played in the communist regime--particularly in its establishment in 1948. Unlike Poland and some of the other regimes in the old Soviet bloc, Czechoslovakia did not immediately fall under Soviet domination after World War II. Czech communists did fairly well in reasonably free postwar elections, and were included in the government of Edvard Beneš, the Czech nationalist who served as president from 1940 to 1948.The Czech reality is that homegrown communists were largely responsible for the imposition of communism after 1948, and the museum does not shy away from that fact.

It is also impossible to escape the Czech sense of humor, which permeates the entire museum. One of its displays, for example, is a communist-era shop, with almost nothing but a few nondescript cans on the shelves. Apart from being historically accurate, this is a highly comic choice, and it draws some of its power from its humor. It reminded me of the comments our wonderful Czech guide, Helena, would make whenever we'd pass an example of what she liked to refer to as "socialist architecture": "Coming up on the right is something no one should see," she'd wryly say. "So please, close your eyes."

The museum, like the Czechs themselves, does not play everything for humor, not at all. The re-creation of a secret police interrogation room and the display telling the story of the 1968 Soviet invasion make that readily apparent.

But the humor is never far removed from the tragedy. It is that sense of balance--the knowledge that comedy and tragedy are not opposites but integrally related parts of life--that gives this museum its character.

The absence of basic necessities is no joke. Nonetheless, walking down a hallway, you pass this picture tucked away in a little nook. At first it appears to be a bit of socialist realist "art," but then you read the caption: "Like their sisters in the west they would have burned their bras, if there were any in the shops."

Working my way through the museum, with its largely chronological approach leading inextricably to the amazing events of 1989, it was hard not to feel a touch of American triumphalism. You move from the dreary existence of the 1950s, through the brief optimism of the Prague Spring, only to see it brutally snuffed out by the Soviet invasion. You learn of the repression of post-'68 "normalization," and thrill at the rise of the Charter 77 dissidents and Vaclav Havel. Then the forty-year Czech nightmare comes to an end, and the people embrace the liberal values that the U.S. stood for in the Cold War.

Upon arriving at the gift shop and looking for some postcards to take home as souvenirs, I came across this one that seemed to capture just that pro-American sentiment. "We're above McDonald's--Across from Bennetton--Viva La Imperialism!"

It's a funny card. It takes such glee in mocking Lenin, one of the original critics of imperialism. I had to buy one.

I kept rummaging through the shop, and found a couple of collections of Soviet-era anti-American and anti-capitalist propaganda posters, spending far too much on them and rationalizing that I could make use of them in class one day.

And I made one last purchase. Another postcard, but this one had a message significantly different from "Viva La Imperialism!" The two of them together tell, I think, a meaningfully different story than either one does in isolation.

"Come and see the times when Voice of America was still the voice of freedom." Now there's a quick cure for the American tourist's sense of triumphalism. I have no way of knowing when exactly this card was first produced and therefore can only guess at what particular events or policies produced it, but there is no escaping its message of disillusionment with the post-cold war U.S.

There was that sense of balance again. Even in a museum dedicated to demonstrating the failure of the ideology of America's Cold War nemesis, there was a refusal to indulge in a mirror-image worship of America's victorious ideology.

What I took from the museum, what I took from much of the reading I did to prepare for the trip (in particular works by Ivan Klima and Milan Kundera), what I took from my admittedly brief and superficial exposure to the Czechs, is that it is the uncritical embrace of ideology--perhaps as much as the content of that ideology--that leads people to destructive fanaticism. If we take our ideas so seriously that we cannot laugh at ourselves and see the humor in the sometimes absurd manifestations of our own beliefs, that is when we lose our way. I'm sure that's not a uniquely Czech view of life, but I saw enough of it there to associate it with the lovely city of Prague. That, as much as the beauty of the city itself, is what I think I'll most remember.